-- A Cyberspace Review Of The Arts

Volume 21.02

May 21, 2014

|

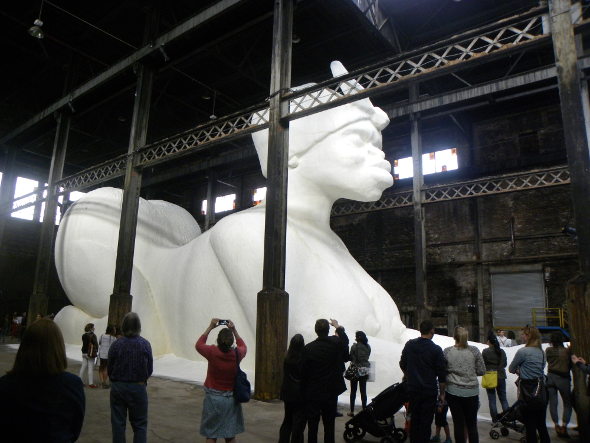

Sugar, of course, was the original mainspring of slavery in the New World. Before the sudden expansion of Western European power in the 15th and 16th centuries, slavery was dying out. In the New World, first gold was hunted; but then it turned out that there was a material more interesting than gold which could be grown and harvested by slaves. In any case, the gold (and the land) were simply stolen from the Indians, who were then murdered. There wasn't that much gold. King Cotton would come along later. In between, major powers fought wars to get control of the places where sugar would grow, and to get slaves to do the work. Sugar was a component of what came to be called the 'triangular trade': sugar (and alcohol made from sugar) for guns; guns, most useful for their business, traded to African slavers for slaves, along with some of the alcohol; the slaves imported and made to work, and die, to harvest the cane and make the sugar. (The United States won at Yorktown, and thus secured its independence, partly because a French fleet, on the way to the West Indies for a really important war, stopped for a few weeks to give their American allies a hand by preventing the besieged British from being resupplied. For the French navy, it was a sideshow. For the United States, along with slavery, it was a cornerstone and an icon. When you look at our sphinx, you are looking at a Founding Mother.) So that is part of the context of sugar, and of Domino, and of this installation. You probably knew all that already; they teach it in every grade school, do they not? The artist, Kara Walker, calls her installation in the former Domino sugar factory 'Subtlety'. We will see whether it is subtle. The formal or physical properties of the installation are impressive. One enters a large industrial space, several stories high and hundreds of feet long, which is nearly empty except for a single lone machine, some platforms, the installation, dominated by the major sculpture, and the dwarfed audience. Scattered about the space are a number of small statues of Black children, the sort of thing one might have had in one's garden, perhaps, in the not-so-distant past, but a bit larger.

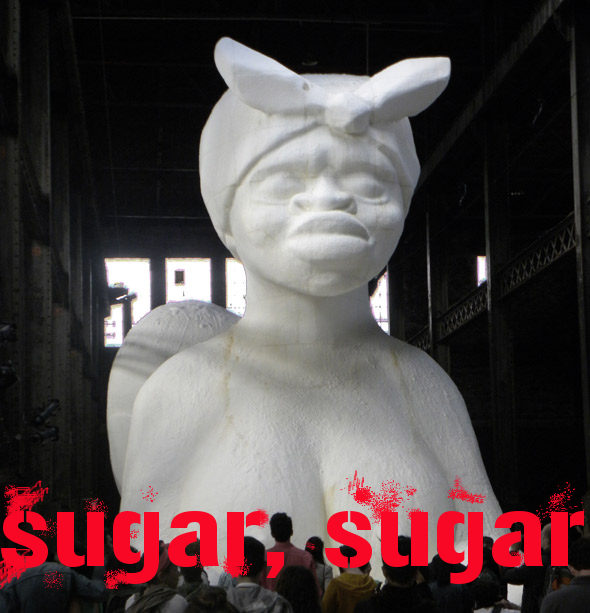

The sphinx itself towers over its viewers, nearly filling the vertical space available to it. While it is clearly based on the sphinxes of old, there are deviations from the traditional Egyptian model. For one thing, instead of the visage of a quasi-royal or divine being, the head is that of a Black servant, and to drive the point home, it is topped by an Aunt Jemima-style kerchief. The face has exaggeratedly African features: very thick lips, and a small, turned-up, button nose. The brows are slightly knitted in seeming anxiety, and the corners of the lips almost tremble between anxiety and ingratiation. One can make no mistake about the caste of the person it depicts. The pose, with the shoulders raised and back, is such that massive breasts are exposed. Both arms are extended forward in a sphinx-like pose; both hands are clenched in fists with the fingers turned down. The left hand shows a curious gesture, with an elongated thumb inserted between the index and middle finger. A great many inconclusive opinions were available as to the significance of this gesture.[1]

The work is certainly popular. On a pleasant Sunday afternoon, at about 4:30 pm, there was a line of about 300 people, and I waited half an hour or so to get in. Nevertheless, because of the huge space in which the installation is placed, there was no crowding. People were able to move around freely, to photograph (this is encouraged), to discuss, to point out, to take selfies with the sphinx as a backdrop, to wander about the antique industrial space, now a sort of unaccountable mammoth of a bygone age. Above and beyond its formal properties and its crowd appeal, what does it convey? Ironies abound, even for Williamsburg, and perhaps subtleties as well, when we consider the multiplicities and complexities which meet in this installation. They will not attract, or indeed even reach, every observer, but they are there if we choose to witness them. Consider the opportunity to create such an installation. Domino did not sell the factory because it was unprofitable, but because more profits could be made by taking advantage of the inflated real estate market of New York City and especially Williamsburg. As a result, hundreds or maybe thousands of people were thrown out of work, most of them out of low-wage jobs which would give them little mobility in the local economic order. Many of these people, being Black, Puerto Rican, Dominican, West Indian, or Central American, are descendants of the very people who were enslaved to make sugar and thus build America. (Walker took care to have a sign erected dedicating her installation to the thousands of people who worked at the factory over the years, who made the factory and the business, many of whom are now out of luck, a part of that now fading part of America that worked and made something.) So Domino and the real estate developers who are going to turn the factory into high-tech, high-priced real estate might be said to have paid to get kicked in the teeth, very metaphorically speaking, by a major artist. Do they care? They probably like it. Art draws people with money and sanctifies what might otherwise be inexcusable. Unlike angry Rockefeller having Rivera's mural destroyed because of Lenin's face [2], they're hip to the public relations and real estate value of liberalism and tolerance. Besides, communism is dead, isn't it? Today's rebels and disrupters are welcome at MoMA, than which there cannot be a more class-bound and elitist institution, even in New York City, and they can bring Lenin along for tea if they can find him. More generally, the demise of the sugar business in Williamsburg can be taken as a synecdoche for the whole onslaught of gentrification which has been especially aggressive in Brooklyn, and with it, the larger picture of the increasing gap between the rich and everyone else that drives it, the deindustrialization of the country, and all that those developments portend. Melting sugar indeed. In the ancient world, the sphinxes posed riddles which were fatal for those who failed to answer them correctly. Here is one: 'In my end is my beginning; in my beginning is my end.' 'Album'A Collection of photographs from the Installation CoordinatesThe Domino Sugar Factory can be found on Kent Avenue in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, just north of the Williamsburg Bridge. It is open on Fridays from 4 to 8 p.m., and on Saturdays from 12 noon until 6 p.m. The entrance is indicated by prominent signage. Notes

[1]

Wikipedia says, 'Fig sign is a gesture made with

the hand and fingers curled and the thumb thrust

between the middle and index fingers, or, rarely, the

middle and ring fingers, forming the fist so that the

thumb partly pokes out. In some areas of the world,

the gesture is considered a good luck charm; in others

(including Greece, Indonesia, Japan, Russia, Serbia

and Turkey among others), it is considered an obscene

gesture. The precise origin of the gesture is unknown,

but many historians speculate that it refers to

female genitalia. In ancient Greece, this gesture was

a fertility and good luck charm designed to ward off

evil. This usage has survived in Portugal and Brazil,

where carved images of hands in this gesture are used

in good luck talismans,[10] and in Friuli.' I was

not able to find any dictionaries of the gestures of

American Negro slaves, but given their predicament,

I have no doubt they had a rich gestural vocabulary,

and I hope someone recorded it.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

all sculpture by Kara Walker, 2014 text and photography by Gordon Fitch, 2014 |

|||||||||||||||||

Back to the Front

Back to the Front