|

What do you do after you've overthrown everyone's

notions of art back to the Parthenon, impugned

Western Civilization, and caused assassinations

and revolutions? Or are alleged to have done so,

greatly to your sales advantage if not your artistic

reputation?

Andy Warhol, or at least his reputation, faced this

question in the later years of his life. After you've

shaken everything by bringing a sculpture of a box

of Brillo, identical visually to its models, into a

high-art gallery and said, "This is Art", and

made it stick, you probably can't just bring another

box of Brillo in next week and next year and so on.

The first box was the one with the Pow!

Further Brillo boxes would soon become a standing,

rather corny joke. "Okay, Brillo, we get it, Andy,"

bored cognoscenti would soon be murmuring.

Before long Warhol said he had given up painting (another

put-on.) He was going to make movies and

photograph-based society portraits.

|

|

Fibers

|

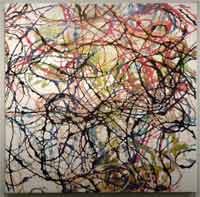

Actually, Warhol never stopped painting, and never

stopped being artistically authentic and "original"

in spite of all the put-ons and put-downs. The world,

however, had changed; he was one of those who had

changed it. And so asked to do an illustration for a

fabric manufacturer, he tangled up a lot of wool, took

a picture, silkscreened it, and turned out something

that had the looks, even the rhythm, of one of Jackson

Pollock's better pieces.

At one time, a trick like that would have made a

stir in the art world. But by the time it was

shown, although it might be great art, it could no

longer shock anyone. The bourgeoisie still wanted

to be properly epatéed and they

weren't going to get it from a Pollock knock-off,

however clever. But it's art -- the

art part of art, rather than the commerce,

the social standing, the celebrity, the

mystification. And besides being an enfant terrible,

a "holy terror", and the scourge of Western

Civilization, Warhol was also a "real" artist, and

one interested in such things has some reason to go

to the show at the Brooklyn Museum. What they

will see is always interesting and sometimes

moving.

|

|

"Rorschach"

|

This is is not to say that the Old Warhol is completely

missing. Not abandoning the Duchampian ethos

completely, and in fact referring rather pointedly

back to the works of "R. Mutt", Warhol and his

friends pissed on a collection of pure copper plates

and pigments which then turned into various shades

of splashy green and blue the way copper does when

it's exposed to something exciting. A little further

down the aleatic road, Warhol and company made some

rather imposing

"Rorschachs"

-- those staples of

1950s pop psychology and innumerable jokes of the era

("I don't know, Doc -- you're the one with the dirty

pictures!") These Rorschachs are several feet high

and wide and tend to dominate whatever space they're

in with their mysterious, symmetrical, abstract forms.

Pictures of Warhol making the paintings assure us that

they were pretty random, just the folded paper with

an ink blot in the middle, but on a very large scale.

There are quite a few 'camouflage' paintings

which are another excursion into total, seemingly

free-form abstraction, and yet they are obviously

quite carefully done in military style, presaging

the military theater of our own era.

There are also a number of large blow-ups of very

small parts of photographs of ordinary objects which,

because of the degree of magnification and severity

of the cropping, look like pure abstract art (and

in most cases, even when we know what they are,

do not yield represented objects to the viewer.)

Most photographers have manipulated their prints

to some extent, whether in the developing pan and

the enlarger or more recently in their computers;

these paintings represent that bag of tricks being

taken to its natural limit and placed on a very large

scale, with results that would delight the Abstract

Expressionists, or at least make them very jealous.

|

|

"Warhol/Clemente/Basquiat: The Origin of Cotton"

|

Besides the move toward Ab-Ex and minimalism, Warhol

also explored the world of graffiti: there is are a

series of collaborations with Basquiat and others.

These tend to be large playful monsters and they

look mostly Basquiatish rather than Warholian to me.

Typically Warhol would screen something and then let

Basquiat work out over the screen print. However,

Warhol later said that Basquiat had gotten him

interested in painting again, so he must have picked

up a brush or two during the process.

One aspect of the late works is the appearance

of religious images and motifs. Warhol was always

interested in the most popular images and it is

not remarkable that he chose cheap reproductions of

Da Vinci's "Last Supper" to work from, particularly

the image of Jesus which is at its center, which

he drew or traced in elementary outline form from a

reproduction and then used repeatedly. The Da Vinci

painting shows the moment when Jesus reveals to his

apostles that he will be betrayed by one of them;

while the apostles recoil in confusion, Jesus himself

looks down and a bit to the side, apparently resigned

to his fate. This image is used over and over again

in a surprising variety of contexts.

|

|

Christ 112 Times

|

:

One of the more striking examples of his religious

work is "Christ 112 Times", Christ being the detail of

Da Vinci's 'Last Supper' mentioned above in a golden

yellowish orange on a black or very dark background.

Each of the Christ-images is about 20 inches high

by 16 inches wide, and they are arranged in a grid 4

images high and 28 wide, so the size of the overall

painting is 6 2/3 feet high and 35 feet wide.

The museum displays this gigantic painting to

great advantage in a large room on the 5th floor,

so arranged that as you walk towards the room and

enter it, it is as if curtains were pulled back

dramatically to the side and the whole is suddenly

revealed in all its power. Next to it is a more

conventional series of copies of the Last Supper; the

image of the black-and-white reproduction is doubled

and painted over a brilliant pink or yellow ground;

the color modifies and further distances the

reproduction of the reproduction from the viewer.

It is tempting to treat Pop Art as almost

entirely ironical, regardless of the talk about

love of beer cans and gas stations in the sunset

glow. However, it is doubtful whether Warhol's

religious paintings can be fully understood in

this light. In spite of all the sex, drugs and

rock'n'roll going on around him, Warhol was an

observant Byzantine Catholic, a frequent

churchgoer, as had been his Rusyn parents. Having

come face to face with violent death, he may well

have had his mind on eternal things throughout the

later period of his life.

In spite of all this, an ironic -- maybe doubly

ironic -- note can be found in some of the religious

works. In one case Christ-images repeatedly overlay

motorcycles, corporate logos, and what looks like

supermarket advertising. Does this mean Jesus is

just another product? In another installation (not at

this show, but in the catalog) there is a sequence of

punching bags designed along with Basquiat, each with

the same image of Christ on it. Most strikingly,

an advertisement for a cheap home-study course in

boxing showing a crouching boxer is overlaid with

the Christ image; the latter comes through only after

one first sees the boxer. Part of the advertisement

is the slogan "BE SOMEBODY WITH A BODY." We have

not only the contrast between a young pugilistic man

eager to make his mark in the world and the resigned,

pacifistic Christ, who perhaps we are supposed to

punch or think of as a puncher with "A BODY" but we

are reminded as well that in the early centuries of

Christianity Roman Catholicism struggled with Arianism

and Gnosticism to establish a concept of Christ which

was at once fully divine and fully human, so that the

physical existence and sufferings of Jesus became a

primary aspect of the Church's teachings.

While Warhol was probably not a student of early

Church history (although you never know) he would

certainly have been reminded of the physicality of

Christ by his religious upbringing. Every time Warhol

went to mass, he would have heard the priest intone

'This is my body ...' during the ritual of

Communion. Therefore, presenting Christ superimposed

on a boxer, or on a boxer's punching bag, is a kind of

irony, but it is not lightly or dismissively ironic;

instead, the viewer finds that his own concept of

Christ or at least of the Christ-figure has been

profoundly challenged. If it is irony it is a

very deep sort of irony.

|

In the same room are some large paintings made

from one of Warhol's favorite self-portrait images,

one with a dire expression on his face and his wig

askew, some of the strands of hair standing straight

up in the air. Most striking among these is one in

which, over a violet ground, the image is doubled

by superimposing a positive and a negative screen of

the photograph on the canvas. One can't help but be

reminded of Man Ray's famous double image of Countess

Luisa Casati.

|

|

Besides these impressive paintings, the museum has

put up some Interview covers and is showing

some of Warhol's television programs in a roomful

of monitors. These are quite popular, but I think

they belong more to the celebrity-infested middle

period of Warhol's artistic evolution than to the

late paintings. There are also some revisitings of

works from an earlier period, like a 2 x 2 Black

Marilyn.

It's nice to see that the Brooklyn Museum has

rescued Warhol the great painter and designer from

the shadow of Warhol the Holy Terror and Warhol the

Pop metacelebrity. The latter may draw crowds

and make for best-sellers, but art-the-real-thing

belongs to the former.

|