Richard Poussette-Dart

by Juan Seoane Cabral

In the years after the Second World War there were two major interpretations of the Abstract Expressionist Movement. Viewing the retrospective on Richard Poussette-Dart at the Guggenheim Museum brings to mind the thought that if an artist didn't find his place in either of these two critical schools of thought, he would irremediably lose his place in the history of art.

The first interpretation was a radical construal delivered by Clement Greenberg. In his opinion, which later became dogma about modernism, the medium-specificity of this recently conceived art movement was the ultimate achievement of painting itself. This idea was persuasive especially because painting was, by then, an art form that had lost its protocols and that was inevitably enervated under the all-devouring power of Kitsch.

The second reading of Abstract Expressionism was conveyed by Harold Rosenberg. According to him, the new artistic form was an arena in which to find (rather than represent) a symbolic and universal Animus, explained by Carl Gustav Jung as the universal coding of images and mechanisms of perception inscribed in mankind's unconscious.

In their clarifying, however mandatory, appreciation of this new art, both Greenberg and Rosenberg shaped the scrutiny that contemporary and future critics would use to analyze the artworks of the Abstract Expressionists. Over the years, with the aim to grasp and make comprehensive a century of eclectic and incoherent art, Academia reduced the names of the Abstract Expressionist movement to an opposing conjunction of celestial bodies. On one side of this solar system Jackson Pollock and William de Kooning offer an array of medium-specificity and gestural work; on the opposite side Mark Rothko and Barnet Newman remind us of the primitive and the search for a spiritual imagery devoid of physical connotations. In the center, acting as the sun, the universal force of the Unconscious produces the gravitational forces of the bodies.

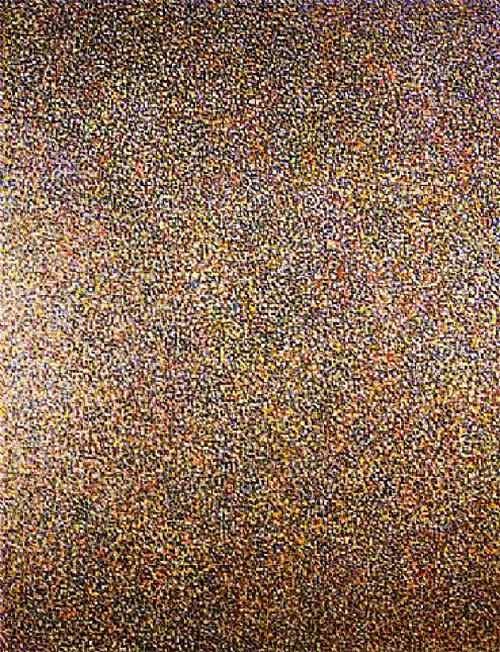

Gesticulated as Pollock, self-confident as de Kooning; uncomplicated as Newman, and detached from the material world as Rothko, Richard Pousette-Dart's paintings recall both critical statements about Abstract Expressionism and seize on many aspects of this particular aesthetic. In their aspiration to use heavy impasto as an expressionist device, his works approve the Greenbergian physical instance of paint. 'Amaranth Garden #2' (1975-76) is a prime example. In this painting, the obsessive mark-making is as important as the colors. There is no subject matter represented, nor can we find a logical compositional device. Yet there is a perpetual exchange between the complex and the basic, as we can appreciate in the relationship between the overall impression of the painting and the clear brush-work that distinguishes one color from another. Also, there is an ongoing dialogue between the cosmic and the mundane. Given Pousette-Dart's bent towards astronomical affairs, it's not impossible to find the awe for the stars in the heavens above inscribed in most of his works on display at the Guggenheim exhibition.

Amaranth Garden #2 (1975-76) Acrylic on canvas.

On the other hand, 'Blue Center Presence' (1960-61) stands for the Rosenbergian search for an event of spirituality. This painting has an intuitive approach similar to the one that drove the masters of the Middle Ages to the concept about light seen in cathedral stained-glass work. The sunlight passed through the glass window without touching it, in the same way that the Holy Spirit impregnated the Virgin Mary without imperiling her immaculate condition. By the same token, the church visitor would have received Jesus the savior into himself by being exposed to the sacred light of God. 'Blue Center Presence' takes lightness itself as motif. It's not only that the artist is refining his search for an image to a description of the luminal qualities of painting. Overall, Pousette-Dart is taking painting to a stance of disembodiment. Perhaps it's in this same opposition to the materiality of the oil medium that the artist has finally found the relish of a kind of painting devoid of physical connotations. Though the presence of the canvas itself denies such an idea, in front of these paintings it's fair to think of a genuine expressionistic approach reduced only to the essential elements. In apparent accordance with Pousette-Dart's distanced attitude towards the art world that surrounded him, this reduction to the indispensable can be taken also as his aesthetic belief.

back to Contents page

back to Contents page