The Soul In Painting

by Michael Thomas

Richter was born in 1932 and lived through WWII in the countryside near Dresden. Two uncles were killed in the fighting and the Nazis euthanised a mentally disabled aunt. He studied art at the Dresden Academy and after seeing Documenta 2 in Kassel, West Germany, where he first encountered the New York School of Abstract Expressionism, he fled East Germany in 1961. Growing up under two dictatorships led to his lifelong distrust in any ideology.

In 'The Daily Practice of Paintings, Writings and Interviews' (1995), Richter says, "I believe in nothing. Through personal experience one must try, undogmatically, to translate one's passion into reality. The first impulse towards painting, or art in general, stems from the need to communicate, the effort to fix one's vision, to deal with appearances, otherwise the work is pointless and unjustified, Art for Art's Sake. Art is making sense and giving shape to that sense. Art serves to establish community. It links us with others and with the things around us, in a shared vision and effort. My concern is never art, but always what art can be used for. Not knowing where one is going, being lost, being a loser, reveals the greatest possible faith and optimism. To believe, one must have lost God. To paint, one must have lost art.

Richter helped organize a group show of young artists in Düsseldorf in April 1963 where he announced his identification with Pop Art. In 'Daily Practice', Richter says, "Pop Art recognizes the modern mass media as a genuine cultural phenomenon and turns their attributes, formulations and content, through artifice, into art. Pop Art has rendered conventional painting with all its sterility, isolation, artificiality, its taboos and rules, entirely obsolete and has achieved international currency and recognition by creating a new view of the world.

"As a boy I did a lot of photography and was friendly with a photographer who showed me the tricks of the trade. For a time I worked as a photo lab assistant: the masses of photos that passed through the bath of developer every day may well have caused a lasting trauma. Then I went to Dresden, to the Academy, and did nothing but paint, in a realistic style. One day a photo of Brigitte Bardot fell into my hands after I went to study with Gotz in Dusseldorf. I had had enough of bloody painting, and painting from a photo seemed to me the most moronic and inartistic thing that anyone could do…(but) even when I paint a straightforward copy, something new creeps in, whether I want it or not, something that I don't really grasp.

"When I draw a person or object (from life) I have to make myself aware of proportion, accuracy, abstraction or distortion and so forth. When I paint from a photo conscious thinking is eliminated. I don't know what I'm doing. The photo is the most perfect picture. It does not change; it is absolutely autonomous, unconditional, devoid of style. A photo is taken in order to inform, what matters to the photographer and viewer is the result, legible information. It is very hard to turn a photo into a picture simply by declaring it one. I have to make a painted copy. I paint like a camera.

In the "Eight Gray" show presented at the Berlin Guggenheim in 2002 [1], Richter equates "gray, a 'non-color', with nothingness, with denying any possibilities for association, differentiation or interpretation," yet the work at the same time, "represents the multiple possibilities and fractured images that more closely imitate our relationship with the real."

Is this a case of having your cake and eating it too? People complain about Richter's ambiguousness, certainly evident in 'Gerhard Richter: Four Decades' (Michael Blackwood US 2002), an interview with the artist walking through the retrospective of his work held at the MoMA, Feb-May 2002. It felt like the artist didn't want me to really see him and know him. Is he hiding behind his paintings of photographs? Projecting a self-protective cool? Is he protecting himself from the violence of Nazism and the wounds of a divided Germany? Is he connected to a life force bigger than himself and his own limited perceptions? That he seeks to connect with in his art and express so that he might share it with others that they might also be inspired?

Soulless and Soul

Webster's New World dictionary defines soulless as "lacking soul, sensitivity or deepness of feeling; without spirit or inspiration." And soul as "an entity which is regarded as being the immortal or spiritual part of the person and, though having no physical or material reality, is credited with the functions of thinking and willing, and hence determining all behavior; the moral or emotional nature of man; spiritual or emotional warmth, force etc., or evidence of this [a cold painting, without soul]; vital or essential part, quality or principle [brevity is the soul of wit]."

Daily Practice

I don't think it was an accident that sitting next to 'Daily Practice' on the reference library pick-up shelf was 'A Zen Life: DT Suzuki Remembered' (1986). My online library search had led me to Richter's 'Daily Practice', which interested me because I practice meditation. I was disappointed to find nothing about meditation practice per se. But I was delighted to find Suzuki's biography and I think his life work has some relevance to the question of soul in painting.

Suzuki describes satori, awakening, as a "childlikeness that has to be restored with long years of training in the art of self-forgetfulness. When this is attained man thinks yet he does not think. He thinks like the stars illuminating the nightly heavens; indeed he is the stars."

Asked at a private party in Chicago, "Why does the Occidental mentality emphasize the objective, while the Orientals are involved in the subjective?" Suzuki replied, " But is there any objective without the subjective?"

"Suzuki repeatedly taught the importance of returning to the basic experience prior to the dichotomy between subject and object, being and non-being, life and death, good and evil, in order to awaken to the most concrete basis for life and the world. Zen is this nondualistic awakening. Logic (the Greeks taught us how to reason) starts from the division of subject and object; and belief (Christianity's teaching) distinguishes between what is seen and unseen. With Zen, reason or faith, man or God, are swept aside as something veiling our insight into the nature of life and reality.

"Awakening to non-discriminative wisdom or prajna-intuition gives a proper foundation to and energizes analytic thinking, which separates self and other, subject and object, man and God. Knowing, being and loving/compassion are united in the discrimination of non- discrimination.

"After practicing meditation for some time you will find yourself in timelessness and spacelessness like a dead man. When you reach that state, something starts up within yourself and suddenly it is as though your skull were broken in pieces. The experience you gain then has not come from outside but from within yourself. You have stood at the extremity with no possibility of choice confronting you. (Man's extremity is God's opportunity.) There is just one thing you must do.

"The moment of coming out of samadhi (a non-dualistic state of consciousness in which the consciousness of the experiencing "subject" becomes one with the experienced "object" and thus is only experiential content), of awakening from it, is prajna, and seeing samadhi for what it is, is satori or awakening and enlightenment.

In 'Zen Buddhism, Selected Writings of D.T. Suzuki' (1956), Suzuki describes sumiye, Japanese Zen brush painting. Thin paper absorbs much of the black soot and glue and water ink, brushed on spontaneously with a brush of sheep or badger's hair. "No deliberation is allowed. No erasing, no repetition, no retouching, no remodeling, no "doctoring", no building-up, no chiaroscuro, no perspective. The artist must follow his inspiration spontaneously and absolutely and instantly as it moves in an attempt to make the spirit of the object move on paper. Each brush-stroke must beat with the pulsation of a living being. It must be living too."

The Soul in Painting

Suzuki doesn't use the words "soul in painting" but he does talk about the art of forgetfulness and becoming the stars.

Isn't this the deepest yearning that people on earth have, to become one with life and the universe, no longer divided, subject and object, no longer alone, childlike in our awe and delight at being alive?

Does Richter's art do this? Or are his paintings of photographs and of the color gray (compare to Yves Klein's blue paintings in the 50's and 60's, radiant and transforming in their blueness), a way to distance his self, his soul, and us from the "horrors of reality"? He writes, "Art transforms violence into myth and deals with death by beauty." One is reminded of Andy Warhol's silkscreens of newspaper disaster photos and wanted men posters and color-decorated iconic celebrity photos, the distanced voyeur in an age of objectified exhibitionism.

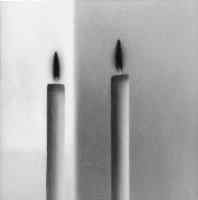

I wonder if Richter's beguilingly beautiful photorealist painting of two candles burning (see attached 'Two Candles' 1982 oil on canvas 140 x 140 cm, private collection) against a divided dark and light background might be an unconscious attempt to illuminate the split between his mind/body and heart/soul? There does seem to be a disconnect in his work. He doesn't care what he paints as long as there is some "I like it" (commercial?) reason to do it. The Atlas project is gray scale painted reproductions of 48 black and white photos of men's heads from a book. No sense of sitting for portraits and the artist trying to "capture their soul."

I suppose you could say that Richter does illustrate the soulless times we live in. All meaning is given to the object, and consumerism is glorified as the new act of communion. Where is the passion Richter talks about? He and Andy may be very successful artist persona illustrators of life in the 20th century but they don't connect my soul to the stars the way Vincent does in 'Starry Night, Cypresses and Villages' [oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm, 1889, in the MoMA collection]!

Vincent's father was a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church. When Vincent was 25-28 years old, he taught school and worked as a lay preacher for the poor in the Borinage coal-mining district in Belgium, before deciding to become an artist.

Richter writes, "Now that we do not have priests and philosophers anymore, artists are the most important people in the world… art is wretched, cynical, stupid, helpless, confusing… I believe in nothing." Notwithstanding the nondualistic nature of nothing, it would seem Richter himself would agree his art is "soulless." It begs the question, is his work "pointless and unjustified, Art for Art's Sake?"

Postscript

These notes grew out of an exchange of e-mails with Robert Sievert. I had mentioned seeing two documentary films on Gerhard Richter at the annual Canadian Art Film Series and Symposium, February 2005, in Toronto: 'Gerhard Richter' (Granada UK 2002), a conversation with the artist in his home and studio; and 'Gerhard Richter: Four Decades' (Michael Blackwood US 2002), an interview with the artist walking through the retrospective of his work held at the MoMA, Feb-May 2002.

Robert's reply was that he found Richter's paintings "soulless." I asked Robert what he meant by "soulless" and before I got an answer became quite intrigued and did some reading and sent another e-mail which inspired Robert to ask me to write something for artezine. Thank you Robert for this opportunity to have so much fun trying to answer my own question! I'm still waiting for your answer! Finally, I confess my own bias that good art uplifts the spirit. And great art uplifts all our spirits. I have referenced the following sources:

- Internet websites

- Webster's New World Dictionary, Second College Edition

- The Daily Practice of Painting, Writings and Interviews, 1962 - 1993, MIT Press 1995. When I found this book on Richter I immediately wondered if there was any connection to the "daily practice of meditation" and turned to Zen Buddhism

- A Zen Life: DT Suzuki Remembered ed. Masao Abe 1986

- Zen Buddhism Selected Writings of D. T. Suzuki ed. William Barrett 1956

Text copyright © Michael Thomas 2005

back to Contents page

back to Contents page