-- A Cyberspace Review Of The Arts

Volume 19.10

August 7, 2012

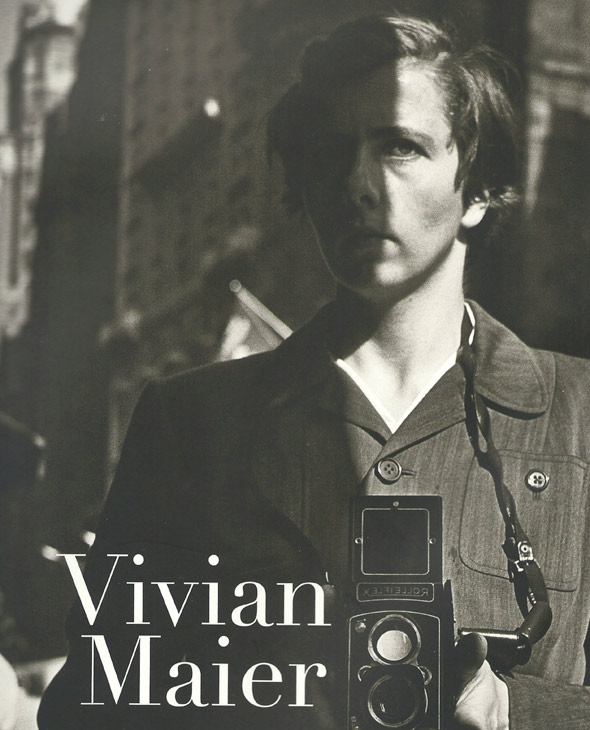

All photographs on this page are by Vivian Maier and are copyrighted in her name.

Like a figure in a dream, Vivian Maier begins to disappear even as we catch sight of her. With one ambiguous gesture she points out our world and shows us things that were always there, but which we had never seen; with another, she declines our questions and steps back into the darkness. We want to call out to her to wait, but the dream silences us, and then she is gone forever. We turn and, scattered all around us, see the objects of her work, an enormous treasure we will spend years, even lifetimes, trying to order and decode. About Maier herself, we can mostly only guess.

Critics and connoisseurs, with a few exceptions, seem to have trouble assigning her work to its proper corner. They know it is great, but it is not easily handled or categorized — or bought and sold. For one thing, Maier did not want to show it to anyone, even to herself; the great body of it is unprinted negatives, and indeed much of the film has not even been developed. Even her closest 'associates', the children for whom she served as a nanny, were unaware of her artistic practice, although they knew she carried a camera around whenever she went out. But in the realm of photography, it has become the custom of the art world (influenced, no doubt, by the objects available for collectors to collect in the cases of painting and sculpture) to emphasize only the finished prints from the hand of the master as truly authentic, and therefore worthy of attention and high price. (Hence the arguments, on which large sums of money ride, about who printed this Man Ray photograph or that Warhol silkscreen, even though there is no ordinarily discernable difference between the objects themselves attributable to their provenance.)

Besides being physically outside the accepted set of objects considered to constitute serious photography, Maier's work does not fall easily into the aesthetic categories prepared for photographs. The initial reaction was to construe Maier as a 'street photographer' — that is part of the title of the first book of her works, and the way she is described by a number of writers. Indeed, she mostly took her pictures on the streets and similar public spaces, like parks. The standards of this genre call for the supposed veraciousness of the camera to be matched with some peculiarly picturesque (or scandalous) manifestation of public life which the photographer happens to catch because of his quick wits, visual instincts, political sensitivities, mystical inspiration, street smarts, or blind luck. There is certainly this dimension to much of Maier's work, but it misses other important dimensions, like the studied, humanistic depth of many of the portraits (posed or happenstance) and their abstract or formal properties, which range from classical abstraction to its subversive siblings, surrealism and naturalism, sometimes in a single image. Maier played in many, many keys and timbres — often at once. In the picture above, of a man on crutches being helped into a mysterious dark doorway, for example, all these dimensions of artistic power are brought to bear powerfully at once. It is not a picture you are likely to forget.

I am particularly interested in the 'portraits' because in my own experience, one cannot get the kind of mood and bearing many of them convey without communicating with the subject in a complex way, usually requiring time, sociability, and close attention. Unless Maier had some peculiar aura, no longer observable by us, which instantly set people at ease and encouraged them to express some of their normally guarded inner selves, she had to have introduced herself and coaxed them to relax and pose, or, actually not pose, but to allow themselves to be themselves. This seems at variance with the depiction of her as an extremely guarded and aloof personality. One wonders how it came about; it seems to be another of the questions Maier is not likely to answer. We do know that she was not one of those who shoot dozens or hundreds of shots of the same subject, figuring to pick out the best one later in the darkroom or on the computer. Each picture seems to have been considered and unique to its moment.

Beyond the humanist sensibilities of the portraiture, genre depictions, and the Weegee-like slice-of-city-life pictures, there is almost always a powerful sense of formal organization in Maier's work, which is occasionally allowed to run free on its own, a piece of fence, a pile of boxes, or two of New York City's mightiest buildings dancing, it seems, with a fire escape.

Although Maier did not exhibit or even develop her work, and certainly did not communicate with the Art World or anybody else about it, it is known that she had a collection of books about photography and we can assume she was aware of the the work of other photographers, especially of the well-known warhorses of the medium who were likely to get published and written about in her time. Some of her work resembles their themes and interest; however, I have not yet seen anything I would call an explicit allusion, parody, or quotation. Maier seems to have been entirely self-taught and self-reliant. She seems to have made no attempt whatever to interest others in her work for any reason, to get advice or criticism or advancement. We can observe as yet only a small portion of Maier's work, which consists of more than 100,000 images according to their major discoverer and publisher, John Maloof, who found most of them in an abandoned trunk being sold by a warehouse. It is said by some that there seems to be a progression in them across time towards the abstract and also toward a certain degree of what might be called edginess. This is most apparent in the color pictures which she took towards the end of her career. But I find this element, this dimension, in all her work; it is one of the things that make it exceptional. Consequently, I suspect she used the street as a studio, partly because she had no other space in which to work, and partly because it afforded her all she needed.

Maier's pictures are presently available through various paths. One is the aforementioned book, Vivian Maier, Street Photographer. This is a relatively large-format book (10" x 11") which seems reasonably well-printed and well- made. (There were some disgruntled comments on Amazon about the quality of the ink; these may refer to an earlier printing, because I found it more than adequate.) The book is not too expensive and contains over 100 striking examples of her work, one to a page. Most of her photographs fully exploit the ability of her usual chosen instrument, a Rolleiflex, to achieve very sharp resolution through a large lens (enabling the use of high shutter speed), and a large viewfinder matching the image on the negative by means of a parallel system of lenses, so it is gratifying to see that much of this has been preserved through this presentation.

Another book, Vivian Maier: Out of the Shadows, with more information about the artist and further examples of her work, is due to be released in October and may be pre-ordered from Amazon (and probably other vendors). Another way to access Maier's work is through web sites, especially the one set up specifically for her work. These images are not as large, but there are more of them, categorized somewhat differently than those in the book. One can also look at some of the color photographs, which it was not possible to put in the book. There are also a number of collections of her pictures on other sites. The more prominent ones so far are: Finally, if you are fortunate, prints from the collection may be exhibited in your vicinity. Schedule and mailing list forms can be found on the various Vivian Maier sites. Other links:

Also, there are a large number of images and videos available by searching Google Images, YouTube, and Vimeo for 'Vivian Maier', for example http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ZlDnzk4-Rg

A few weeks ago, somewhat earlier than predicted, I received the other Vivian Maier book, mentioned above. This book represents a different tranche, one might say, from Vivian Maier, Street Photographer; it comes from a different trunk or box, discovered by a different person, and has been organized somewhat differently in that the writers have sought to derive a kind of narrative from what they found, both in the photographs and in the detective work they have done on the facts of her obscure life. The various mysteries that surround Maier have already inspired quite a few narratives, some rather fanciful, of the sort which total ignorance makes possible. However, the authors ot this book have actually found things out about Maier's childhood in France and her career in the United States as a nanny and secret photographer, which is quite another matter. The format, like Vivian Maier, Street Photographer, is a big squre book, although a little smaller, following the format of the Rolleiflex image. There is more print in it, as befits the ambitions of the writer, but it is by no means print-dominated. The pictures are allowed to speak for themselves. I think it is safe to say that those understand the power of Maier's work will want both of these books. Although they are basically the same kind of book, there is very little intersection between the sets of images, in contrast to what is often the case with other highly-regarded artists, where every editor and every publisher feels obliged to throw in the usual warhorses. No doubt we have thus far seen far less than the tip of the iceberg here. There are supposedly some 100,000 negatives; between the two books, the web sites, and the shows, at most a few hundred have thus far been published. With regard to this body of work, It is wild-surmise, silent-upon-a-peak-in-Darien time. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gordon Fitch, 2012 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Back to the Front

Back to the Front