Judith Schaechter:

Andromeda

Judith Schaechter:

Prometheus

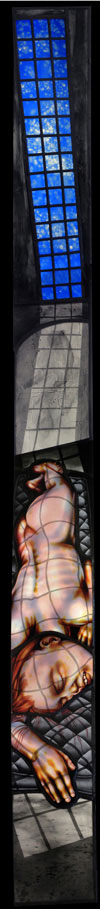

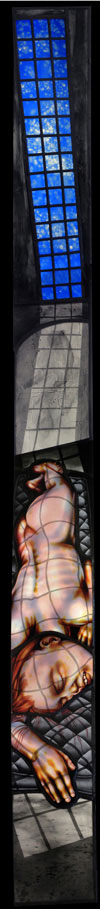

Judith Schaechter:

Magdalene

Judith Schaechter:

Mother

Judith Schaechter:

Sister

Judith Schaechter:

Daughter

|

Eastern State Penitentiary is not really a prison

any more. It was built in the early part of the 19th

century and was designed on very different principles

than the prisons you have seen in the movies and

the media (or directly). The general layout was

based on Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon, but instead of

every cell being constantly observed from a central

point, only the hallways of the long, low buildings

which contained the cells were centrally observable.

There was not much concern for watching the prisoners

because they were supposed to pass almost all their

time in what we would call solitary confinement,

as an aid to their repentance -- the prison was,

after all, literally supposed to be a pentitentiary,

a place of penitence and reformation.

The only light entering the cells came from narrow

windows above, four by 40 inches. In the time before

gas and electrical lighting, they must have been

just about the only light the prisoners saw, except

for an occasional watchman's lantern. The narrow

windows, which prevented escape, also aptly echoed the

constraint the prisoners must have felt in the narrow

cells. The only things outside the cells a prisoner

insiade could see were the sky, the sun, the moon,

clouds, and perhaps a few passing birds. In a way,

probably deliberately, the cells are curiously like

the cells in a monastery. It was these narrow

windows, and some others positioned vertically,

into which Schaechter installed her works.

This arrangement was supposed to be more humane than

previous methods of imprisonment and punishment.

The actual prison buildings were surrounded by a

high stone wall with faux-medieval towers which were

more to impress and warn outsiders than to keep the

insiders inside.

Over the years the theories of prison management

changed; general solitary-confinement methods

were abandoned, more buildings were added to the

complex, new kinds of structures, like a greenhouse,

a chapel, a synagogue, and an infirmary were built,

and some more traditionally prisonish superstructures,

like watchtowers, were added. Then, in 1971, the

penitentiary, already obsolete and in poor repair,

was vacated and began to fall apart in earnest.

It quickly became an overgrown ruin, used mostly by

colonies of feral cats. Subsequently, it came to

be understood that the site was important

at least historically; the trees were cleared away,

some of the decay was stopped, and it is now what

one might call an arrested or suspended ruin. It has

been turned into a kind of archaeological site, not

from the ancient world but from an earlier phase of

our modern era. Enough is done to keep the interior

from decaying further, but no attempt has been made

to restore the buildings generally or pretty them up.

One of the uses to which the penitentiary has been

put has been the siting of artistic installations,

especially those which reflect or reflect upon prison,

after all an enormous fact of our national life.

Judith Schaechter was one of those who got an

opportunity to construct one of the installations.

But as a Philadelphian, Schaechter was already aware

of the Penitentiary and had already thought that it

would be an ideal place for the kind of work she does.

Traditionally, stained glass has been the province

of religious institutions and occasionally has been

employed as decor in the mansions of the wealthy or in

large public institutional structures. [1]

Schaechter's work, however, goes in another direction.

It is resolutely secular

and personal. In the case of the installations

at the Penitentiary

generally persons taken out of mythology

and legend are depicted: Andromeda, Prometheus, Mary Magdalene,

Atlas, and Noah in one area and Icarus in another.

These are more like examples than symbols. She also

installed three windows depicting those who suffer

when others are imprisoned: the Mother, the Sister,

and the Daughter, and finally a large window with

over 96 characters, 'The Battle of Carnival and Lent',

depicting the struggle between impulse and restraint,

or between Energy and Reason as William Blake might

have put it.

Throughout most of the 20th century, modern, or at

least Modernist, art was suppose to take place on

stretched canvas or on other traditional media; or

at least, this is what the big names did. That restriction

began to break down in the 1960s and '70s, as popcult

with its multifarious and irreverent ways invaded high art, and artists

explored a great variety of materials and methods,

some of them recently invented, others ancient.

What was old became new again.

The resurrection of stained glass was one of these

new-old developments. Especially when installed

so that it filters ever-changing external daylight,

it has qualities of natural luminosity, reflectance

and vitality which no other material can claim.

It is, however, obviously difficult to work with,

especially when one wants to provide close detail.

In this area, one approach has been to paint the glass

with translucent materials, but Schaechter generally

goes another and better route: she uses something

called 'flash glass' where only a thin layer of the

glass is colored, and thus can be etched away to provide

different tones and shadings. Also, she often assembles a

work out of more than one layer of glass, making a

variety of colors possible. Unlike painted glass,

the coloring and shading of etched and layered glass

is virtually eternal.

(Glass is not Schaechter's only medium, but it is

mainly what she has been doing for the last 30

years.)

The complexity of execution does not distract this

artist from constructing work with important formal,

emotional, and spiritual characteristics. Indeed,

her work has been sometimes criticized as 'morbid'

or 'depressing' by those who would prefer art, or

at least stained glass, to be pretty. Schaechter's

work is more serious than that.

Indeed, to some extent, Schaechter says in one of

her commentaries on her work, the people who were

in the prison were one of her imagined audiences.

Hence, for instance, the repeated appearance of birds in the works

that compose this installation; they would have been

the only forms of life the earlier prisoners

would have been able to see through the narrow

windows, as well as being an essential element in

some of the stories.

(The idea that the world of man is a prison, or that we are

all in a kind of prison if any of us are, is not

all that far-fetched, of course.)

The first window completed was that depicting

Andromeda. Andromeda, in classical Greek mythology,

was the daughter of Cassiopeia, who boasted that

both she and her daughter were more beautiful than

the Nereids, sea spirits who were often the companions

of the sea god Poseidon. In retribution, Poseidon

began to destroy Cassiopeia's country. An oracle told

Cassiopeia that the country could only be saved if

she sacrificed her daughter to the sea monster Cetus.

Andromeda was duly chained to a seaside rock to await her

fate. Fortunately, her fate turned out to be the

legendary hero Perseus, who killed Cetus, rescued

Andromeda, and married her. Later, Athena placed

her in the heavens as the constellation Andromeda,

which turned out by chance to include the

great spiral

galaxy of the same name invisible to the ancients,

but which on closer view was seen to be another 'island universe'

like our own Milky Way, leading us on to previously

unimaginable spaces. Thus has Andromeda suggested innumerable

astronomical and science-fiction adventures. (Although Andromeda is

a passive character in the classical story, her name

means 'Ruler of Men', implying that the story may have

been rewritten in antiquity for political or religious

reasons. In any case her name seems to have come true.)

Needless to say, an exciting story like this,

including a young, beautiful naked woman chained

to a rock, and possibly a noble hero and a monster,

appealed greatly to artists then and subsequently,

if only as an irresistible excuse to paint a shapely nude in

various contorted postures. Not all the works

were so superficial: Joseph Cornell compounded the

mythological with the astronomical and the surreal

in 'Hotel Andromeda'; and

Rembrandt

went beyond ogling

to depict the suffering and terror of the victim.

Schaechter's Andromeda belongs to this latter class.

Sweat, tears, or possibly the seawater kicked up by

an approaching monster run down her anguished face.

We also see the starry sky of her future in the

background; her chain rather reminds me of the chain

in Joseph Cornell's depictions.

Prometheus is in a nearby cell. He brought

or restored fire to mankind against the will of

the gods, and was punished by being chained to

a rock and having his liver torn out daily by

a divine eagle. (Since Prometheus was an

immortal titan, it grew back to be torn out

again. You will be glad to know Prometheus was

eventually rescued by Hercules.)

Promethus has been a favorite of those who

admire defiance of authority, or at least those

instances of it which are sufficiently far away

and long ago. Schachter's Prometheus is not the

noble fellow you will see in a lot of painting; he

is another prisoner, another sufferer, and shows

it, burned by the fire which he carries, and

threatened by the attack of the immortal eagle.

His is the anxiety-laden look of the point man:

indeed, his name means 'Forethinker'.

Atlas is nearby. A titan like Prometheus, he

was condemned by the gods to hold up the sky

forever. Since the sky was envisioned by the

ancients as a sphere, the image was often taken

to be the Earth instead. He is the prisoner of

the heavy burden, astral and terrestrial, that

he carries forever.

Noah is here, not the zookeeper of religious

children's stories but the anguished prisoner of

the Ark, the Flood, and his own human failings.

Finally, there is Mary Magdalene. Her particularly

striking window shows her as a prisoner stretched

out prone and naked, on a mattress in a prison cell;

behind her is a barred window (a window within

a window). The shadows of the bars lie across her

naked back like the stripes of a lash. The stories

and traditions surrounding Magdalene are complex

and contradictory. In many, she was said to have

been an eventually reformed prostitute; and so, the

'Magdalen Society of Philadelphia', founded a few

years before the Eastern State Penitentiary, as an

institution to rescue and sustain 'fallen women',

that is, prostitutes, from the streets and, of course,

the prisons, punished for the guilt of others.

Another section of the installation, named

'Flight Risk', featured Icarus, who was given wings

by his engineer father, and flew fatally close to

the sun. This window was made by putting an engraving

of a man on red flash glass and an engraving of a

bird on blue glass together. They were then cut into

strips to fit the format of the long, thin apertures.

The name 'Flight Risk', refers not only to the risks

of flying but to law-enforcement terminology with

which the prisoners of yesteryear would have been

all too familiar.

The imprisoned, in formal prisons, anyway, have

usually been men; often forgotten are those whom

they leave behind in personal prisons of their

own when their male family members are locked up.

Schaechter shows three of these: a grieving child,

sister, and mother.

One critic remarked of 'Sister' that her diaphanous

nightdress and underlying nudity implied an unsisterly

relationship, but I felt that the implication was one

of vulnerability, not erotic attraction. If there is

an erotic element, it is not the free and joyous kind,

but the kind of the goes on the block to pay a price.

Finally, there is the great

'Battle'

window, based

on the similarly-titled painting of Pieter Bruegel.

The window contains almost a hundred characters

and has to be studied closely and at length.

Like Bruegel's picture, it depicts a struggle between

excess and restraint, but it is not particularly keyed

to the Bruegel version or to some other assemblage

of characters like popular culture or the myths and

legends of antiquity. Instead, each element needs

to be taken on its own and dropped into your intuitive

mind soup. Fortunately, you need not be standing in

Eastern State Pentitiary last Novermber or a future

art gallery or museum to do this;

the image currently available on

Picasa

permits the required enlargement and close inspection.

I've omitted mentioning a set of accompanying smaller

works, called

'Ornaments'

by Schaechter, which appear

on their own accompanying some of the larger windows,

and in the background of others, sometimes squarely

to the eye, sometimes in perspective, and run through

much of her other work. These are intricate, abstract,

usually highly symmetrical figures which deserve an

essay of their own.

Although the Eastern State Pentitentiary installation

has been dismantled and will presumably not return

there, the windows are scheduled to be shown in

May at

Claire Oliver Gallery.

Most will be in light boxes,

but some effort will be made to present at least a

few of the windows in a simulation of their dark,

decayed prison enviroment. The date may change;

it will be advisable to check with the gallery.

Besides the gallery, a

book

is available and there is

the aforementioned

Picasa exhibition.

Take a look. This work is something you won't forget.

1. For example,

Robert Sowers's work at the American Airlines Terminal

at Kennedy Airport in New York City. One might also mention

Gerhard Richter's randomly-colored window at

the Cathedral of Cologne, which makes, it seems, yet one more

effort to create meaning out of the rejection of

meaning where meaning is expected, a well which may

be running rather dry these days.

|

Back to the Front

Back to the Front