-- A Cyberspace Review Of The Arts

Volume 19.04

April 21, 2012

|

Henry Taylor

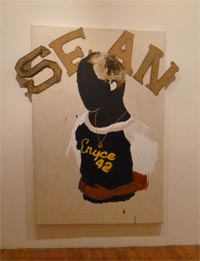

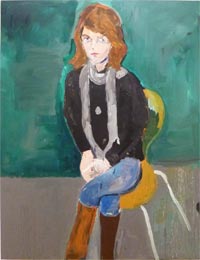

at MoMA/PS1 Henry Taylor, a remarkable artist whose work has recently been on view at (MoMA) PS1, is a native of California. Born in 1958 in Oxnard, he now lives in Los Angeles. He mostly paints figuratively; his most frequent subjects are friends, relatives, neighbors, and sometimes people encountered by chance who provoke his interest or affection. He is also a sculptor or maker of constructions; occasionally, the two genres are mixed, because he often paints on found objects like cardboard boxes. He tends to work quickly and impressionistically. The painting is, by and large, vigorous, direct and succinct. He generally concentrates on design, gesture and expression rather than fine detail and texture. Although his work is in no way derivative, some viewers were strongly reminded of Alice Neel. Perhaps more idiosyncratically, although one of the guards agreed with me, I was reminded also of the late paintings of Andy Warhol and even, somewhat more remotely, of Francis Bacon's. Taylor uses words, often in the form of large block letters cut out of cardboard, or painted or written directly on the canvas. (He also writes on the other side of the canvas, giving explanatory or dedicatory material.)

Perhaps the most important thing, for me anyway,

besides the intrinsic aesthetic value of the work,

was that he gives us a compound point of view that

is pretty carefully omitted from most of the art

I see. It is not only that of the African-American

sensibility, a distinct and particular strain of

American culture, but of the caste or class to which

many African Americans (and of course people of other

'races' as well) are assigned: the one in which the

modern, high-technology prison regularly appears

in the background,

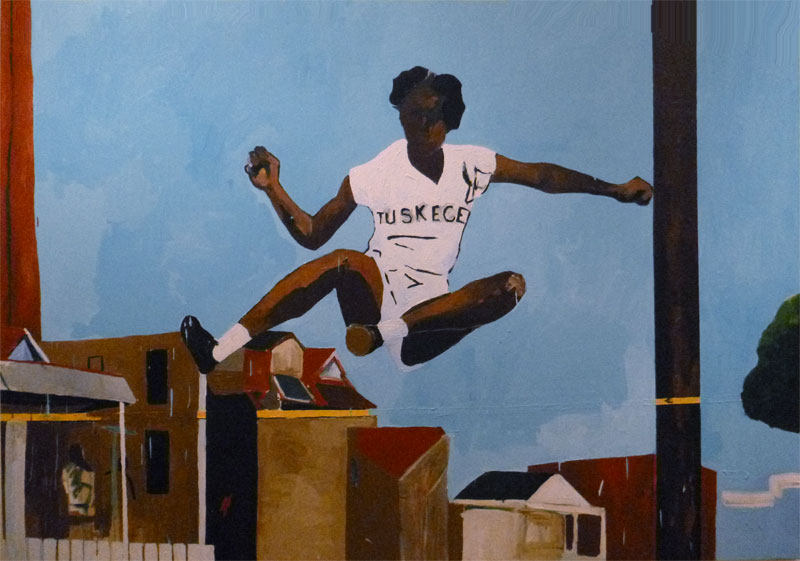

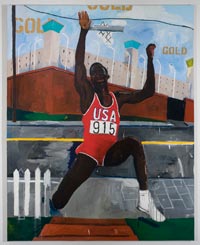

Indeed, before and while studying art, Taylor trained for and was employed as a nurse, an aide in a mental institution, a considerably different point of view than that likely to be experienced by the average middle-class American, and one which clearly brought him insight and empathy for a wide variety of people, including many who are often despised and shunted out of sight. In one room, four large paintings attested to the importance of certain athletes or sports not as mere entertainment but as a kind of liberation in African-American life. Of these, I was moved most by 'See Alice Jump' (at the top of this article), in which a young woman high-jumper seems to sail into a blue heaven above a series of low, dreary urban structures. Jackie Robinson, Jesse Owens and Carl Lewis are also represented; unlike Alice, they are depicted in works with considerable symbolism worked into the design. As in so many other paintings here, a prison appears in the background of the Jesse Owens and Carl Lewis tributes; in the latter, the basketball player just made a layup shot from the sidewalk in front of a modest residential house with a white picket fence and a hopscotch diagram inscribed on the sidewalk in front of it while the prison glowers from across the street. The messages are pretty obvious even if some of us are not familiar with them as a fact of daily life. Taylor has also painted (from photographs) a number of significant leaders and events, such as Huey Newton of the Black Panther Party, and author Eldridge Cleaver. The portrait of Cleaver is dark and rather mysterious and is elegantly designed with rather Modernistic values. Cleaver seems to emanate into view from a dark doorway, holds a cigarette, and challenges us with a glance over his shoulder.

The major work here, at the center of everything, was an installation called 'It's A Jungle Out There.' Mops, brooms, discarded wooden chairs, boxes, boards, bare branches, and other backyard detritus make up the main body of the work. Viewing it, we find ourselves the back yard — the home truth — of American culture. Within it, large plastic bottles of the sort in which detergents and disinfectants are supplied, mostly painted black and supported by sticks — probably mop handles — look like people lost within it. Here and there we see a note scribbled on an object, sometimes a name, a memo, a plaintive message to some absent person. Off to one side is a doll's house or bird house, dark as if seared or dirtied with great age. On one wall overlooking the assemblage, a companion painting appeared; one in which bears the inscription 'JUNGLE FEVER' but with everything but 'JUNG' almost obscured, reminding the viewer of a connection between the high and the low, the intellectual and the pop, the past and the present which might not have occurred to them. It's too bad the work of this major artist isn't better known, but the defects of our system of artistic production, collection and display have already been noted here and elsewhere. At least Mr. Taylor made it to PS1, which continues to be a lively venue of a lot of very interesting and probably very significant art. * the 1998 murder of James Byrd Jr., a Black man dragged to death behind a pickup truck by White supremacists in Texas. |

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Gordon Fitch |

||||||

its wall bearing the admonition

that warning shots will not necessarily be fired;

the one where a forest is made up of mops and brooms

and blackened detergent bottles on sticks like so many

heads lost in it; where a chain attached to the back

of a truck bespeaks not ordinary work but atrocity*.

its wall bearing the admonition

that warning shots will not necessarily be fired;

the one where a forest is made up of mops and brooms

and blackened detergent bottles on sticks like so many

heads lost in it; where a chain attached to the back

of a truck bespeaks not ordinary work but atrocity*.

Back to the Front

Back to the Front