-- A Cyberspace Review Of The Arts

Volume 18.05

May 20, 2011

|

Facetime #2

at Parker's Box This last April, Parker's Box, a gallery at 193 Grand Street in 'downtown' Williamsburg (ask the proprietors for the complicated origin of the name) hosted an interesting cross between paper art (drawings and watercolors), video, and one might say performance art in 'Facetime #2', one of a series of two-person shows in which the artists are invited to reflect one another's work. The drawings faced each other at a right angle on the north and west walls of the gallery's main space, while in the opposite corner, three videos played continuously on three television monitors. The works were not produced independently in parallel, but rather out of an ongoing set of communiqués (mostly mediated via Tumblr) in which messages and images flew back and forth between the two participants as they worked. The result was a rather complex structure of both signification and mood. This is one advance in the rather complex narrative of artistic Postmodernism which, far from fading out, seems to be taking root and drawing sustenance from the communities in which it is now embedded. One of the aims of Modernism, at least for awhile, was to eliminate narrative from pictorial art both internally and externally. Abstract expressionism was held to be pure mind, the end of the road that started in Lascaux and went past the Parthenon; indeed, Rothko said that he and his peers were working on the art of the next thousand years. Within the works themselves, the representation of objects, the illusions of depth, movement and mass, and so on could be seen as tricks played on the viewer. Although he only occasionally played the Modernist, Andy Warhol probably summed up the Omega Point of this movement when he told a reporter who asked what was 'behind' one of his paintings, 'There's nothing behind it. It's just what you see.' It had turned out at that point that not non-representation, but the representation of banal objects banally presented (although with very strong formal values -- sneaky!) was what was required to empty pictorial art of narrative, of literary or symbolic meaning. It seems to have been the end of that particular road. In every end is a beginning, and subsequently a diametrically opposed idea seems to have become dominant in the post-Modernist artistic era. Instead of the purity of representation-free form, we find all sorts of connections, stories, representations, 'meanings' one might say, in every sort of picture and object and event. 'Only connect' has been the slogan of our new era. Stuart Sherman, reviewed in a previous issue, is one example, an artist who placed a great, almost cabalistic weight of meaning on the seemingly small backs of extremely simple objects, drawings, collages and texts. He was not alone. Conceptualists have gone as far as endowing non-existent things and ideas with complex meaning. A Buddhist would be sorely tempted to observe that the emptiness of art-as-emptiness had emptied itself out and thus become full. In the present Facetime exhibitions, the Parker's Box Gallery chose to raise this complexity to a new dimension; the exhibition consists of work produced collaboratively by two artists, not in the sense of two or more persons working on a single piece or a succession of them, but in the sense of two artists reflecting one another's work in work executed in simultaneously and, in a sense, in the same space. This sort of thing is not entirely unheard of; one thinks of Picasso and Braque working together with Picasso lifting Braque's rather harmonious, classically reposed abstract forms and skewing them, showing him a thing or two, I suppose, as they painted side by side. However, the present exhibition is the first one I have attended where the works were deliberately purposed towards an performance of precisely that reflectance. As a result of the collaboration, many themes or motifs were passed back and forth between the artists. Among these were stadium lights, birds, wiring and sound equipment, stacked-up television sets, animals, a large stationary crane, a greenhouse, a sailing ship, and plants of various kinds. A good many of the drawings were inscribed with brief texts. While both artists definitely preserved their distinct styles and concerns, their works formed a considerable network, a web, one might say, if we were to think of each idea or motif connected to its opposite numbers on the adjoining wall by a virtual string. Given the complexity and depth of the situation, I am going beg off giving a total description and instead try to recount the way in which a single motif or thematic element works through the objects of both artists, picking stadium lights for my example.

The most prominent example of the stadium lights motif is in Vainsencher's rather dramatic and surprising video, of which a few frames are shown here. The video consists mostly of apparently still images which are moved about stop-motion-wise and upon which low-tech animations, produced by painting, are superimposed or mixed. This video were backed up by two rather lower-key videos on two supporting monitors made by John Roach, in which such images as flowing water were seen, but in heavily processed form, so that they tended to be seen as often calligraphic abstractions except for their fluidic movement. In that particular environment, their relation to Vainsencher's video might be analogous to someone singing backup harmony, although they could also stand alone in their meditative repose.

Like many large urban artefacts, stadium lights seem gestural, signifying, even portentious, without however conveying any clear message. For example, they can remind us that sport, even in an out-of-the-way low-rent park, is no longer mere fun and games but serious, institutionalized business costing many dollars and burning many watts. Basketball courts lit by these angels of mechanical illumination are supposed to distract ghetto gang-bangers from criminal acts, becoming thereby politically crucial appliances necessary for public peace. They are, of course, a crucial element of America's variegated night games, some official and others not.

Even abandoned they can seem like sleeping giants or still potent idols. Indeed, they hark back to the most primeval of all statements: Let there be light! At the same time, their is nothing mystical or spiritual about them; they are usual naked frameworks of metal on which a battery of large industrial artifacts, the lamps, are affixed, supplied with electricity by large, industrial wiring. The industrial-grade light they produce cannot be looked at close-up; instead, they function to make ball games playable on fields of hyped, fluorescent green. Vainsencher's video take on these lights is, one might say, explosive: sometimes they bloom like flowers, sometimes emit streams of luminous goo which inundates their little universe. Others appear to be boxed in, mechanical. Although I'm publishing just a few frames above, you can see the full videos on Vainsencher's personal web site.

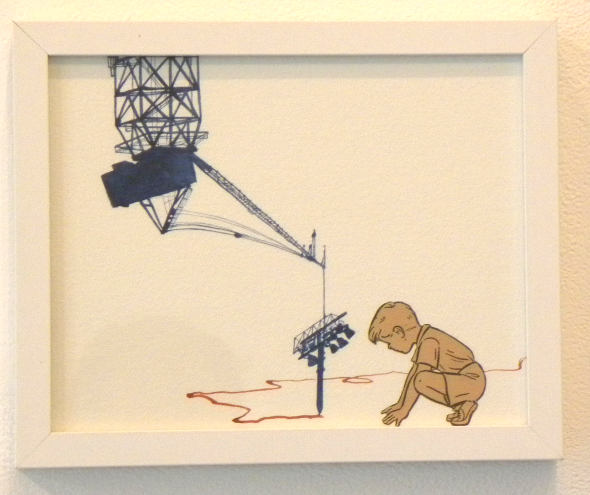

John Roach's take on these monsters is wryly surrealistic. The monsters are mastered, domesticated into toys a child can play with. In one drawing one is being dragged about by an Erector-set crane which is itself bound to a series of impregnable codes, like an illustration in a Martian dictionary. In another, the crane-stadium lights assemblage has been turned upside down to form a writing instrument that amuses a child. (Although what it writes is an uneasy red stream!) In yet another case, the streaming version of the lights flow out into a countermonster, a sort of cloud-elephant that is more than their equal.

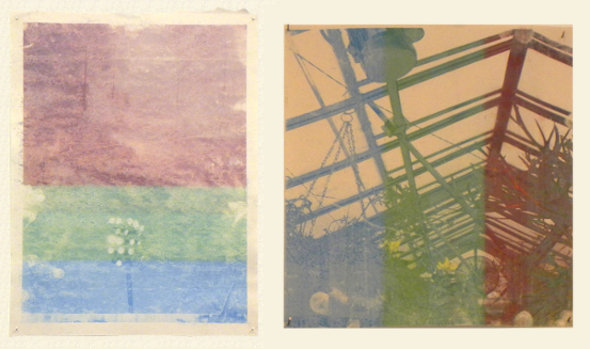

The story of the stadium lights does not end here; they also appear in Vainsencher's drawings. Here, they hang mystically from a nail, or recede into three-colored mists, in harmony with some other similar artefacts.... (I could have gone with the birds, but they would have been even more mysterious.)

About the Artists NOTE: The artist's web sites mentioned below are not mere calling cards or glossy brochures. They contain a lot of material by and about the artists, including current work and exhibitions. Vainsencher in particular has been doing an extended work consisting of one drawing or other image per day posted immediately on the site. John Roach was born in San Francisco and now lives and works in Brooklyn, N.Y. He has worked in a variety of media, including painting, drawing, electronic and low-tech sound structures, and video. Most recently, he participated in the Self-Destroying Art event at the Flux Factory, and at the Sequence of Waves event at St. Cecilia's Church in Greenpoint. Website: www.johnroach.net Gabriela Vainsencher was born in Buenos Aires, lived and went to school in Israel, and now lives and works in Brooklyn, N.Y. In 2010 and 2011 she participated in 'An Exchange With Sol LeWitt (Mass. MoCA and Cabinet Magazine, Brooklyn), 'Flat Files Artist of the Week' (Pierogi Gallery, Brooklyn), 'The Work Office Two' (The Work Office, N.Y.), and 'Housebroken' (The Flux Factory). Website: www.gabrielavainsencher.com

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Gordon Fitch |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Back to the Front

Back to the Front