Travels and Everyday Life

by Hearne Pardee

In 1922, the critic Paul Rosenfeld advised Marsden Hartley that he would have to return to his origins in Maine, to his personal roots, in order to fulfill his artistic potential. Rosenfeld, reflecting ideas expressed by Alfred Stieglitz, believed that American artists needed to study and interpret their most familiar surroundings, to which they had the deepest psychological ties. Only then could they develop an art comparable in expressive power to that of the Europeans.

Although Hartley did return to Maine and paint some of his best work there, I've always been skeptical of Rosenfeld's injunction that somehow only this literal return to his home would enable Hartley to tap the deepest sources of his creativity. Perhaps it's just the idea of a critic ordering an artist around, but something in this nativism, this myth that our connection to place is implanted at birth, seems related to the inward turning of American culture in the period between the world wars, to a suspicion of European ideas and culture. Hartley has always inspired my admiration for his efforts to join his American and European experiences, by going to Provence to paint Mont St. Victoire, or remembering New Mexico in Paris. Hartley incarnates the increasingly rootless existence of artists today.

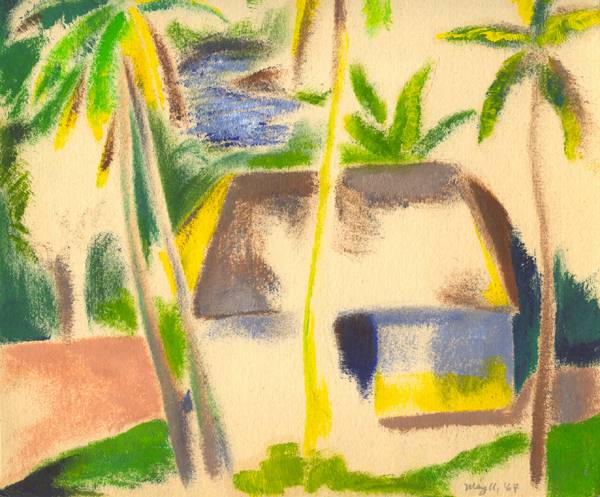

In my own case, my work as a painter began in a very distant place, on the island of New Caledonia, a French colony in the South Pacific. When I was in college, I taught art there in a Melanesian village, encouraging the children to make pictures of their surroundings, and of stories and topics that interested them. I myself, having just discovered Cézanne, made my own paintings on cheap pieces of cardboard, attracted by subjects like the banana plants near the door of the tiny kiosk where I stayed, by the houses with thatched roofs across the way, or by the groves of trees that grew along the river. Siorem, the teacher I worked with, once looked at them and interpreted the areas I left blank (one trait of Cézanne's style I had successfully appropriated) as clouds of mist rising from the valley.

I keep these paintings as evidence of my early interest in the everyday landscape and see in them preoccupations I work with today, such as houses and yards reduced to areas of color - still inspired by Cézanne. But what interests me more than the paintings themselves is an experience I recorded in my diary that marks my achievement of "belonging" in that place, a place so foreign to my home in suburban Pittsburgh.

It was the rainy season then; the air was heavy with moisture and smoke, and the ground was sticky with gray mud. The shiny banana leaves by the guesthouse drooped and glistened. The guesthouse, or kiosk, was an octagonal building of white stucco, with a conical thatched roof in the old Melanesian style. Behind it were coffee groves that also functioned as toilets. Water dripped down my neck as I brushed between the slender trees, and the ground was covered with wet leaves. There was water everywhere. Back of Pierre's house, just opposite the kiosk, was the steep embankment of a small stream; I slid down to fill a pan with water and struggled back up, nearly losing my claquettes in the mud. I went back into the kiosk and shaved. Still weak from my stomach cramps during the night, I lay down again on the camp bed by the open window. Sounds of rushing water and rustling leaves mingled with voices, the cries of children and the barking of dogs.

Pulawa came by the kiosk, arms chugging like pistons, imitating a truck. He caught my eye from the window and broke out laughing. He and another teenager from the island of Lifou were going down to swim, and they asked me to come along. I told them I would come a bit later.

Despite my uneasy stomach, I followed them along the path through the coffee groves, down to the brown, rain-swollen Houaïlou River. I liked its surging waters; I took off my shirt and claquettes and jumped in with my shorts on. I wanted to throw myself into this new way of life, to immerse myself in this place.

Siorem came and joined us in the water with some younger children. He played a game called "Wolf", in which he chased the children, clinging to a bamboo raft and then ducking under. They shrieked as he pursued them under water, and there was something truly scary when his dark, close-cropped head re-emerged, with eyes partly closed, veiled by the drops he shook from his glistening face.

The bamboo rafts provided our only access to the outside world. By the pebble beach on the other side was a dirt road that led to a fence, which protected the village from the cows of the colon Mazurier. In the fence was a wooden turnstile, and beyond it a parking area where visitors to the village would wait while rafts were sent to fetch them. Twice a week, M. Galinié, the col-porteur, a traveling merchant, would park his truck there. Opening doors on the side of his truck, he displayed an array of canned goods and household supplies. The little parking area became a market square, where 20-franc notes were exchanged for provisions.

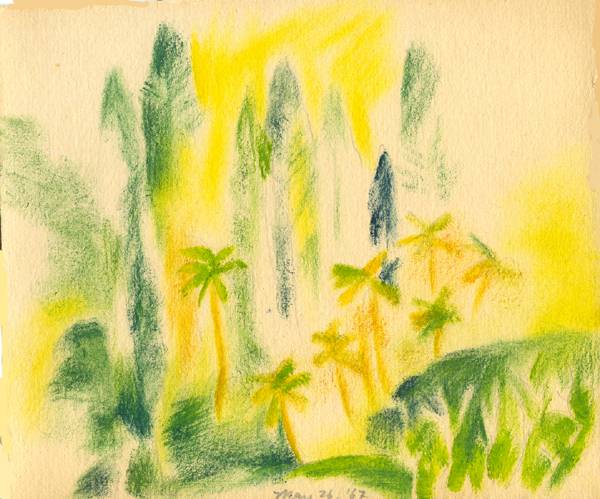

The dirt road continued on past a grove of palm trees and tall araucaria pines, with their distinctive, slim silhouettes - a silent, special place that had once been the center of the village, marked by a tall house at the end of a ceremonial path, before it had been displaced across the river. I would walk through the grove and out to the metal gate by the main road, where I sat in the grass with my paints and tried to depict the mass of trees, rising up against the backdrop of mountains. The abandoned grove endowed the landscape with history, like Roman ruins in Claude Lorrain - with a sense of loss and nostalgia.

But my real connection to this place came through the Chief's wife, Aline, a tall, aristocratic woman with lanky, muscular arms. I enjoyed watching her when I ate at the Chief's house, and I sensed that she liked me. She often carried a child on one arm as she did things, but her eldest son, Ivon, was old enough to be conscripted for military service in France. This was a source of concern.

One day, after having tea, I went with the Pastor and Pulawa to see Galinié - a regular social event on Tuesdays, but also to buy some rice and sugar to donate to the families that prepared my food. Aline was there, tense. She couldn't wait for me to ask. "Ça y est," she exclaimed, "Ivon est parti." He had left that day for the military garrison from which he would eventually go to France. She said it was hard to part with a son who was always around the house, and her eldest. It was unusual to talk so personally. I told her my mother felt the same about me, when I left to go on my long trip to the Pacific.

"I always think about him," she said, and took out her handkerchief. Then, turning back to the truck, she handed some money to M. Galinié. She bought a can of peas, which she handed to me. I accepted the gift, and just said merci as Aline walked away. Galinié, who had observed the exchange, shook his head and said, "Le service militaire, ça brutalise les gens."

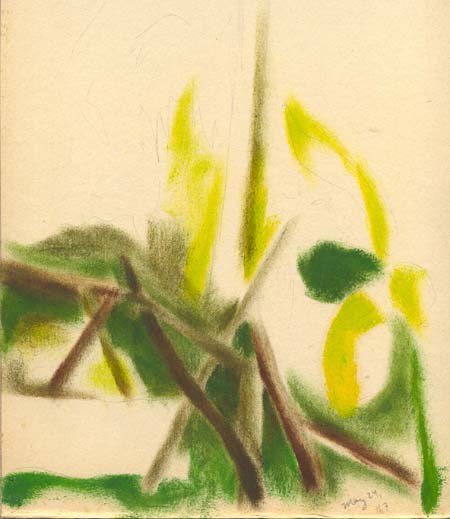

It had always been my role, as a guest, to make gifts to Aline and other hosts. Now, holding her gift to me, I dimly realized that I had entered into a more personal relationship to village society, a sort of symbolic adoption. I grasped as well, by some sort of intuition - perhaps going back to primitive links between adoption by a group and entitlement to shared property - that it entailed a new relationship to the land. Walking back home from the river, I looked down a green, grassy pathway I hadn't noticed before. It led to a clearing bordered by bananas and fruit trees, with the remains of a shack in the middle. At that moment, in the evening light, it seemed to resemble some backyard from my childhood. I couldn't remember the specific place this spot evoked, but it sufficed for me that I could mingle my personal past with this marginal space in the village and claim it for myself. When I saw the children later, playing up and down the hillside of the school, I felt I had found a way into Nessakouya.

I returned more than once to paint that spot. As I look at those paintings today, they seem sincere but slight. Like most of the words recorded in my diary, cryptic comments, they leave out much of what now seems important. The image is largely symbolic - of my longing for home, for maternal embrace - which I couldn't explain at the time, but which I've worked since then to articulate - the sort of deep links to place demanded by Rosenfeld and Stieglitz.

I believe, then, that we connect to place more through the bonds of social transactions than through the mere fact of birth. Hartley, too, it seems to me, formed his bond with the Atlantic shore not so much because he was born in Maine as through his relationship to the Masons, the family that adopted him into their household in Nova Scotia. Hartley bonded with them and shared in the loss of their sons at sea, an experience which haunted him during the final years of his life.

For all his celebrations of Northern archetypes, I prefer to value Hartley for his internationalism, and to take my own experience in New Caledonia as a glimpse of an emerging global perspective. I bring that experience to the suburban landscape of Davis, California, where I continue to seek out marginal homesteads linked to childhood memories. I work outdoors in the Impressionist tradition, which still offers a way to deal with new experience in the context of everyday life. As progress displaces us more and more from familiar places, I focus on the ways in which we weave our memories and experiences together and form new connections. In that process I plan one day to return to New Caledonia and record its present environment, to weave together the familiar and the exotic.

Hearne Pardee

Davis Landscape, acrylic on paper, 24"x26", 2006

back to Contents page

back to Contents page