The Outsider Art Fair of 2006

by Gordon Fitch

Consuelo González Amezcua: In The World (1962; ballpoint pen on paper)

Charles Smith: Angel (early 1980s; wood tar, paint, mop fibers)

Eugene Andsolsek, untitled (1950s; colored ink on graph paper)

John Barton, Love Has A Mind Of Its Own (2005; oil on canvas)

David Borghi, Hide And Seek (c. 1990; oil and pigment on panel)

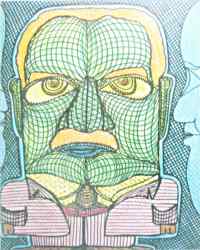

Thomas Burleson, untitled (Head) (c. 1990; colored inks, paper)

The Outsider Art Fair is a once-a-year exposition of art put on by Sanford L. Smith and Associates, who also organize other categorical fairs, such as new art and antiques. A large number of galleries and dealers take booths of varying size in the show, some of them from as far afield as Europe and Asia. As the show's catalog says, "For fourteen years, we have watched our event become central to the field, a place where enthusiasts, collectors and curators continue to gather. It is also a celebration, as 33 specialists from the United States, Europe, and, this year, Japan, unite and present what Roberta Smith, in her 2005 review of the Fair in the New York Times, called 'an annual dose of smelling salts' for the art world. ... The outsider Art Fair again headlines and defines Outsider Art Week in New York City. As always, a number of educational programs, gallery exhibitions, and special events support the excitement of the fair." For example, a number of programs at the American Folk Art Museum.

So what's an Outsider? What is Outsider Art? It has become something of a tradition to ask this question, especially when writing articles like this one. I certainly asked it on my way to the fair. What, in this age of Postmodernity, can possibly be Outside? And does it matter?

Moving through the crowd at the Fair, I asked the question from time to time, and got a variety of answers. One answer is that the artist is or was disconnected from the world of dealers, galleries and museums, but that seemed contradicted by the exhibitors who are, after all, dealers and galleries -- this is no fence show!

The favorite qualification seemed to be that the artist had never been to art school, but this seemed dubious to me -- how would anyone know for sure? Besides, many self-taught artists, perhaps most, aim for a fairly orthodox style and many achieve it. In any case, the rapid advance of technology in our times requires that many otherwise "inside" artists be self-taught; there aren't any schools on the cutting edge.

Residence in mental institutions or at least withdrawal from normal social life seemed about as positive as art school was negative. This was an early common meaning of the term, applicable to people like Wölfli and Darger. Another possibility, related to avoidance of art school, is what we might call naiveté, a departure from the usual techniques and materials which mainstream artists are taught to use by schools or their peers, which brings us to the boundaries of folk or vernacular art, that is, art people make for their own or their neighbor's use without construing themselves as artists doing Art. However, naiveté can be assumed just as surely as social withdrawal and lack of formal training.

So the distinctions seem pretty arbitrary. The degree of what we might call outsiderness between Von Bruenchenhein, who seems to be officially an outsider, and Joseph Cornell, who hung out at Stieglitz's gallery with the famous and fortunate and is now definitely about as Inside as you can get, are pretty minor. Von Bruenchenhein's outsiderness came mostly from the fact that he lived in Milwaukee, which made a walk down to Stieglitz's gallery inconvenient, and never tried very hard to sell anything; he like to keep his work around. However, there is nothing naive about his work, and he lived a rather normal life for a working- or middle-class person in his time and place. He certainly was not as withdrawn or as eccentric as Cornell.

One could argue, of course, that Cornell's work, like Van Gogh's, is of such quality as to rise above stylisitc distinction. But this would suggest that "outsider" means "not so good", and that is very much contrary to experience and observation. For example, in the sub-category of Folk Art there is a sub-sub category of Quilts. Quilting is an old American tradition and can be considered a folk art -- it was practiced by many thousands of people, mostly women, as a normal part of everyday life. The containts of the media and the uses to which the work was put required a kind of simplicity of conception and execution which we now associate with Modernism, although it is probable that most of the quilt-makers never heard of Modernism and would not have thought much of it if they had. Yet if one has any feeling for that kind of design, it is obvious that many of the quilts on exhibition at the Fair, as elsewhere, are of the very highest artistic quality and belong in the Museum of Modern Art next to Rothko and Pollock.

The Fair had other kinds of folk art to show. One artifact I particularly liked was a devil's head made of heavy sheet steel which had once been one of the targets in a shooting gallery. In spite of its simplicity the design had a good devilish feel to it. The head had then been tapped with no doubt many thousands of .22 shorts, giving it a rather peculiar texture, and was coated with generations of shooting-gallery paint. However, authentic folk art has been in high demand for some time, regardless of its aesthetic quality -- purely utilitarian milk cans which only a generation or two ago were put out of sight behind barns can be seen gracing the front steps of posh houses in expensive suburbs. (Plastic milk crates will be next -- better get them while they last!) Outside of the quilts I did not see a great deal of what I would call old-time, traditional folk art.

There was a good deal of work at the Fair which was simply unconventional in its approach to media and execution, but which was not all that unlike some work which one might find in a mainstream gallery or museum. Since the downfall of Abstract Expressionism as the art in the 1960s, there is really no longer a single set of conventions by which art works can easily be divided into official and unofficial categories. For example, the Outsider Art Fair had some very attractive work done in steel of various kinds by Haitian artists, but it wasn't totally unlike the work of, say, Lucas Samaras on the one hand, or traditional African sculpture on the other (except, of course, in price).

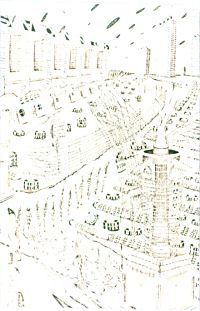

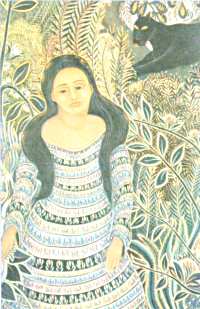

A great deal of outsider art is "visionary" which might be considered another qualification. That is, the artist seems to be attempting representation, whether realistic, impressionistic, or cartoonish, but the scenes depicted are not of this world. Often, broad vistas and mighty cities are laid out in great detail. The surreal becomes normal. Angels descend and devils play. A woman's dress dissolves into an organic network lacing the world. The detail itself leads to another subcategory of Outsider Art, that of "obsessive drawing" or "obsessive art", wherein designs, words, or small images are repeated hundreds or thousands of times.

The Fair did not lack for some genuinely creepy work (no other adjective can describe it), a Darger or two for example, and a small number of works by Wölfli. These however did not predominate. It may be that that sort of work is rare, although it seems also possible that the people presenting works at the fair didn't think it would sell very well in that environment.

In the end, one is overwhelmed by the variety, energy, and originality of the works presented at the fair, and gives up trying to grasp a theme or pass judgement on the fair as a whole or on the works within it. As the writer said, it's a dose of smelling salts, a sudden awakening to the realization that there's a great deal to art besides what is in the uptown galleries. Maybe there always was and always will be. In any case, the only way to figure out the Outsider Art Fair is to show up and take a look when it comes around again next year. Allow yourself plenty of time for the visit, because the fare is as varied and rich as that of one of our major museums.

Gee's Bend: African American Center Diamond Quilt (Alabama, 1950s; cottona)

Chris Hipkiss: In Europe Age Feral (1999; graphite and ink on paper)

Paul Lancaster: Jungle Solitude (detail) (2000; oil on canvas)

Les Barbus Müller: untitled (c. 1940; carved volcanic stone)

Ted Gordon: Little Man, Big Plans (2001; crayon, marker and pencil on paper)

George Widener: Megalopolis (2005; mixed media on paper)

Text copyright © 2006 Gordon Fitch

Images courtesy of Sanford L. Smith and the exhibitors

back to Contents page

back to Contents page